By Jarrett Barrios, Los Angeles Region CEO

Here in LA, as in other parts of the United States, February is Black History Month. While this annual focus on African Americans’ history more often seems to focus on significant contributions of individual African-Americans with biographical portraits, it can also be a time for us to remember (or learn about) historic events impacting African Americans. Studying these sorts of events have real value: remembering history, as they say, is the first step towards not repeating history’s mistakes.

The era I recall in my blog today is the mid-1960’s; the place, the South Los Angeles community of Watts. Founded in 1903, Watts began to grow as did many LA-area communities with great migrations of Mid-westerners in the early 1900’s. According to historical sources, the community became attractive to blue-collar families moving to Los Angeles, but differed from other towns in the greater LA area in that it welcomed white, black, and Latino families. By 1920, 14% of Watts’ population was African American which, according to census figures, was the highest in California.

In the mid-1920’s, Watts was annexed into the City of Los Angeles. During this period in American history, “racial covenants” in property sales were still enforceable. Many of the new suburbs that were being built further out of the Los Angeles city center began attracting white middle-class families; but black, Latino and Asian families didn’t have the same options, and therefore, didn’t have the same freedom to relocate. Because of Watts history of inclusion, it became a growing destination point for the black middle-class through World War II.

After the war, the population in Los Angeles exploded. Like many others moving west, millions of blacks began leaving the South as part of what historian’s call The Great Migration, with many arriving in LA. These racially-restrictive real estate covenants, together with the near-universal bank practice of redlining and explicit refusals by landlords to rent to African-Americans (Title 8 of the Civil Rights laws—known as the Fair Housing laws—would make the denial of housing opportunities based on race illegal in 1968), meant that newly-arrived African Americans had very few options. According to scholarly research of Los Angeles real estate, a staggering 95% of housing in LA’s neighborhoods was restricted against rental or sale to African-Americans (and Asians). But, one neighborhood they could move to was Watts.

In this housing market, racial balance in Watts would soon disappear. Newly-arrived blacks began to move into an increasingly dense community, and white families with more options moved away. Watts’ unusual mixed-race neighborhoods changed. Increasingly Watts was a community of dense neighborhoods with increasingly poorer residents. The delicate social fabric began to fray. Businesses moved away; blight moved in.

In this increasingly depressed community was a growing neighborhood sentiment that beyond just quality housing, many other necessary resources for the community were also not accessible—schools, hospitals and emergency services, equitable policing, city economic investment. By the mid-1960’s, these many factors had combined into a combustible mix.

On August 11, 1965, a routine traffic stop in Watts proved to be the spark that lit up this combustible community. A young African American motorist named Marquette Frye was pulled over and arrested by a white California Highway Patrolman, Lee W. Minikus. A crowd gathered. Tension among onlookers and law enforcement climaxed into a verbal exchange that escalated to physical violence. Almost immediately, deadly and destructive conflict erupted throughout Watts’ commercial district. Homes and businesses burned, and stores were looted. Police shot suspected perpetrators, further whipping up furor. At its height, more than 16,000 law enforcement officials, including the National Guard, patrolled the streets. An 8 p.m. curfew and immediate-arrest policy attempted to quell the unrest. By the time the smoke cleared five days later, almost 1,000 homes had been burned, damaged or looted. Today recalled as the Watts Uprising, the widespread violence resulted in the loss of 34 lives and more than $40 million in property damage. It was the largest, costliest social unrest of the entire Civil Rights era.

Of course, this sad, complex history poses larger questions for how society and, in particular, how government responds to social unrest. For all of us, too, it triggers questions of what policies can mitigate the root causes of such unrest. Ultimately, Governor Pat Brown’s commission investigating the incidents in Watts concluded that “city leaders and state officials [had] failed to implement measures to improve the social and economic conditions of African-Americans living in the Watts neighborhood. ”

Learning this history and knowing the Red Cross was a robust disaster responder in greater Los Angeles during this era, I started to dig around our offices to see what I could learn about the Red Cross’ role during and after the unrest. There was simply nothing to be found, except for a small mention in August 20, 1965 article of the Los Angeles Times, explaining that Red Cross volunteers partnered with individuals and groups from the United Way, the Salvation Army and Youth Opportunities Board to help residents affected by the civil unrest.

Just when I had given up hope, I happened to be in the National Red Cross headquarters in Washington DC, and speaking with 45-year Red Cross volunteers Joe Prewitt-Diaz, originally from Puerto Rico, who shared that he had worked as a young volunteer during and after the Watts unrest.

For approximately three weeks, Joe explained, he been part of a national Red Cross relief effort. Reminding me that Red Cross fundamental principles are to help everyone, he explained that his assignment as a Spanish-speaking volunteer, was to assist with many of the Mexican and Mexican-American residents of Watts:

“Just on the outskirts of one of the areas of conflict, pockets of Spanish-speaking residents were unable to leave their homes and they were without food and water. Along with other volunteers, I traveled to their homes—outside the areas of violence—in a Red Cross Emergency Response Vehicle, to bring them food and water for days. It was hard work, and turbulent at times, but we got basic supplies to the people in need.”

I was happy to hear Joe’s story, but not surprised to learn that we were there trying to help.

Like all history lessons, Black History Month’s inspiration to explore the history of Watts and its historic unrest, seems to ask something of us, too. Knowing something differently—that is, learning something new that changes essential facts in a narrative—can push us to reexamine our own efforts that intersect with that history. For Red Cross, maybe there’s more to do here than food and water, care and comfort. Learning how, in many ways, policies and prejudices created the combustible circumstance that resulted in such violence, I can’t help but wonder about how we are called upon to engage in our work differently.

Red Cross works today in parts of South Los Angeles –as we do in many other communities left vulnerable to disaster as much by socioeconomics and by fault lines and liquefaction zones. Today, we work proactively with community leaders. Instead of waiting for a quake, flood or outburst of social unrest to respond, we seek to partner with community’s “grass tops” leaders before disaster strikes.

Because we are already present in these communities, and increasingly, because our amazing volunteers live in these communities, our role is evolving. We are becoming part of the community we seek to help. Another result of this work is that we are coming to increasingly reflect Los Angeles—the diversity of LA is increasingly visible in our staff, our volunteers and, of course, in our cherished clients.

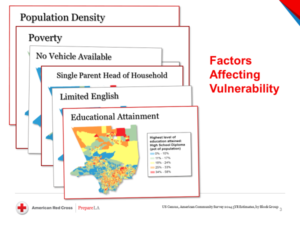

Given that we are an organization of limited resources, how we prioritize our proactive efforts is all-important. Most significantly, we are focusing our community resiliency-building efforts in areas challenged by high unemployment rates, substandard housing, and other social indicators similar to those present before the unrest in 1965. Through our PrepareLA Campaign, we’ve identified some of LA’s most vulnerable communities based on socioeconomic and other factors—the same factors commonly used in public health initiatives and government agencies like the Centers for Disease Control—as indicators of risk. At the Red Cross, we use this data because it has predictive power for where disasters, both small and large, will strike—and therefore, where our resources, pre-disaster, should be focused. In addition, of course, we factor where fault lines, flood zones and liquefaction areas are present to account for naturally-occurring (as opposed to socially-occurring) risks for communities.

Based on these assessments, the Red Cross Los Angeles Region’s PrepareLA program has identified those communities at greatest risk of damage and loss of life following a disaster, and three years ago we began organizing community leaders around building resiliency in the areas most vulnerable to disasters. As our website explains, our PrepareLA initiative is now in 15 of LA’s most vulnerable communities, and much of the work we do is accomplished by community coalitions and community ambassadors, whose grass-roots work drives our preparedness and resiliency messaging and education straight into the soul of every, statistically proven, more vulnerable neighborhood in Los Angeles.

The Red Cross, of course, can’t solve the many contributing factors to social vulnerability, just as we can’t solve the issues that formed the context for the Watts Uprising. However, we can focus our preparedness education efforts on vulnerable communities prior to events that, foreseeably, will lead to damage and death. In FY 2016 and FY 2017 combined, we installed more than 22,000 free smoke alarms in homes throughout the Los Angeles Region, including more than 12,000 in some of the most disaster-vulnerable communities like South Los Angeles, Compton, Westlake/Pico Union, Pacoima, Koreatown, Huntington Park and Bell Gardens. Additionally, more than 26,000 people region-wide have already participated in Red Cross emergency preparedness education programs. This work is our commitment to a safer and better prepared Los Angeles, and to every resident in this city and across LA County.

Jarrett Barrios is the Chief Executive Officer at the American Red Cross Los Angeles Region.

Jarrett Barrios is the Chief Executive Officer at the American Red Cross Los Angeles Region.

To learn more about Jarrett Barrios or the America Red Cross Los Angeles Region, visit RedCrossLA.org.